As this story takes shape, millions of families are mourning the loss of loved ones who died from the COVID pandemic. Families in Texas just spent their first holiday season without their children who perished last May during a school shooting. Still, others mourn the loss of friends and family who perished in countless ways. For families whose loved one passed away at Michigan Medicine, the Office of Decedent Affairs has a team of dedicated social workers to help you through the process. Lizbeth Harcourt, MSW (adult services and the Livingston and Washtenaw County Medical Examiner’s office cases) and LaTresa Wiley, MSW (Mott Children’s and Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospitals) support families up until the decedent leaves the hospital. They also support the faculty and staff of Michigan Medicine as they learn how to better support families and process grief.

The Office of Decedent Affairs (ODA) began in 2007 as a joint effort between the Departments of Social Work, Pathology, Risk Management, Patient Relations, and Legal. The intent was to create a centralized location through which all things related to end-of-life and after-death care flowed. “We create and maintain bereavement materials for families, develop and update policies and procedures for after-death care, serve as a centralized point of contact for questions that families might have after they leave the hospital, specifically related to post-mortem care, or questions they may have about care their family member received up until death. We also deal with unique requests that may come from families and try to support staff and faculty through education and consultation,” explained Harcourt. She went on to explain that people in healthcare have a passion for providing curative care, and when facing end-of-life, palliative, or hospice care, it can be difficult and take a toll on them. Harcourt and Wiley provide training both to help these providers communicate effectively with families as well as to process their own grief.

The Office of Decedent Affairs (ODA) began in 2007 as a joint effort between the Departments of Social Work, Pathology, Risk Management, Patient Relations, and Legal. The intent was to create a centralized location through which all things related to end-of-life and after-death care flowed. “We create and maintain bereavement materials for families, develop and update policies and procedures for after-death care, serve as a centralized point of contact for questions that families might have after they leave the hospital, specifically related to post-mortem care, or questions they may have about care their family member received up until death. We also deal with unique requests that may come from families and try to support staff and faculty through education and consultation,” explained Harcourt. She went on to explain that people in healthcare have a passion for providing curative care, and when facing end-of-life, palliative, or hospice care, it can be difficult and take a toll on them. Harcourt and Wiley provide training both to help these providers communicate effectively with families as well as to process their own grief.

“There are more than 1200 deaths that occur at Michigan Medicine each year, and that doesn’t take into account the thousands of patients that we take care of who pass away in other facilities or at home. We may have been caring for these patients for years. Our healthcare providers may have the skills to process personal grief, but professional grief is different,” Harcourt continued. To address the pain healthcare providers experience with each loss, ODA staff provide continuing education credits for nursing, social work, and medicine. They work with staff, faculty, and learners to build skills and to celebrate the awesome work they do. They also provide an opportunity for anyone at the hospital to express their thoughts on a Grief Wall every May and December. As thoughts are written on the windows, it gives patients, families, and members of the Michigan Medicine community a chance to grieve and heal together.

In addition to their work with those who have experienced a loss of a loved one, the ODA team also participates in Pathology’s Patient and Family Advisory Council, which focuses on encouraging pathologists to interact directly with patients and their families. For example, a pathologist may sit with a prostate cancer or a breast cancer patient and discuss their biopsies with them, reviewing slides together and discussing what the test results mean. It may be a forensic pathologist gaining improved strategies for communicating and delivering bad news to family members who may be experiencing strong emotions.

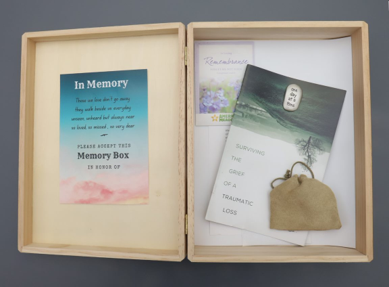

The ODA also has a viewing room for patient families to see their loved ones a last time before they leave the hospital. This is particularly important for families who have chosen direct cremation, as it is their last chance to see their loved one. The family is carefully advised on what to expect and what they should and should not do, then they are allowed to go into the viewing room, while the social worker stands witness to their grief. During the COVID pandemic, however, the viewing room was closed, which made it difficult for families who could not be with their loved one during their last days nor could they be present to say goodbye. To help these grieving families find closure, the ODA, along with the forensic photographers and morgue staff, prepared memory boxes for families. These contain locks of hair, tasteful photographs of hands or tattoos, fingerprints, and/or hand molds along with a poem. These memory boxes become treasured keepsakes for the family, the last “touch” of their loved ones.

“For families who experience a loss of pregnancy and were never able to meet their person outside the womb, we offer them an opportunity to create memories through burial or cremation, if they choose, at no cost to them,” added Wiley. “For families who experience a stillbirth, we provide cuddle cots to keep the baby cool, so families can spend up to 24 hours with their baby bedside, until they are ready for the baby to move to the next stage of postmortem care.” As with the adult decedents, families who lose children are also provided memory boxes that may include plaster or ink hand or footprints, a lock of hair, molds of hands or feet, heartbeat recordings, corded bracelets for fathers, and butterfly charms for mothers. Siblings are provided books to help them deal with grief from the donor-funded Always Remember Pediatric Giving Library.

“For families who experience a loss of pregnancy and were never able to meet their person outside the womb, we offer them an opportunity to create memories through burial or cremation, if they choose, at no cost to them,” added Wiley. “For families who experience a stillbirth, we provide cuddle cots to keep the baby cool, so families can spend up to 24 hours with their baby bedside, until they are ready for the baby to move to the next stage of postmortem care.” As with the adult decedents, families who lose children are also provided memory boxes that may include plaster or ink hand or footprints, a lock of hair, molds of hands or feet, heartbeat recordings, corded bracelets for fathers, and butterfly charms for mothers. Siblings are provided books to help them deal with grief from the donor-funded Always Remember Pediatric Giving Library.

Harcourt related a story to illustrate the impact their work has on families. There was a family whose son died by suicide. In the middle of the night, a police officer alerted the family, who lived a few hours away. When Harcourt arrived in the morning, she learned that the family was on their way to the morgue. Harcourt was able to intercept the family and bring them to the ODA office. The family didn’t have any information and wanted to see their son, but he was under the care of the medical examiner’s office, not Michigan Medicine. “I gained permission for the body to be transported from the morgue to the viewing space and then facilitated the viewing. Their pain was unbelievable. At that acute moment, I was able to bear witness to their pain and suffering. What is remarkable to me, in this and other viewings, is that by the time the family is ready to leave, there has been a shift from that acute emotion to empathy toward me for the job that we do and the service we provide. It is humanity at its best. When someone is acutely suffering yet is able to see someone else in that moment…It is really remarkable.”

The opportunity to educate faculty and staff is particularly fulfilling for Harcourt. “If we deliver news insensitively or provide inaccurate information to families who just experienced a death, that can add to their distress, so it is very important to me that we provide staff and faculty with the skills and information necessary to do this work well and do it right, and that they have confidence in it." She also finds it to be an honor to be present at someone’s most intimate moment of grief. “Allowing for their emotions to come to the surface and just bearing witness and being a companion to the families is so rewarding. I always feel like my role in that moment is to physically and emotionally be a strength, to be solid for them. I am there to physically catch them if they are going to their knees. I think that is really powerful.”