By Beata Mostafavi | Michigan Medicine Health Lab | 1 March

Dr. Raja Rabah, MD (left) with Justin Prybyla and his family.

Dr. Raja Rabah, MD (left) with Justin Prybyla and his family.

Inside the blue, toolbox-sized container resting on top of a large conference table was doctors’ biggest clue to what had gone wrong inside their young patient’s body.

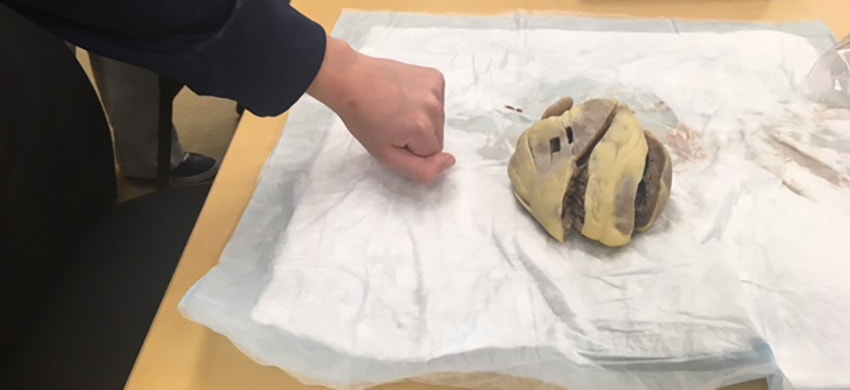

A pathologist slowly opened the box, unzipping a bag and peeling back tissue paper to reveal a gray, grapefruit-sized human heart — one almost twice the size it should have been.

Most of the nearly 20 people in the room were the regular teams at University of Michigan’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital who routinely examined failed hearts at teaching conferences, including pediatric cardiologists, pathologists, nurses and trainees.

But on this day, a special guest also attended: the heart’s owner.

Justin Prybyla sat among clinicians along with his mother, younger sister and two sets of grandparents. The 17-year-old watched multiple experts review his case, presenting slide after slide describing details of what appeared to cause his heart to suddenly stop working correctly the summer before his senior year of high school.

One microscopic image showed the pink spots representing damage from what doctors believe was a virus attack with large chunks of blue in between — areas where his immune system seemingly attempted to fight back.

Then, he watched as Mott specialists picked his old heart right off the table. It was the next best thing to his original wish after his heart transplant in fall 2017: to take his first heart home and save it in a jar on his shelf.

“No one ever gets to see their own heart and mine was out of me, so why not?” Justin says. “I didn’t know what to expect. I think some people might get creeped out, but I thought it was pretty cool.”

Justin Prybyla's heart on the table.Justin is among a handful of pediatric heart patients who, after expressing interest in seeing their old heart in the flesh, have been offered the opportunity to do just that.

Justin Prybyla's heart on the table.Justin is among a handful of pediatric heart patients who, after expressing interest in seeing their old heart in the flesh, have been offered the opportunity to do just that.

After all, the defunct organs receive lots of scrutiny.

“The heart goes to pathology for review, where they make a report and then present what they learned. This is a really important educational opportunity for us to learn more about what made the heart sick and information that could possibly help another patient in the future,” says Mott pediatric cardiologist Kurt Schumacher, M.D.

“It’s definitely unusual for a patient to come to these meetings, but it’s something we’d like to offer to more families who have that interest,” he adds. “This is not for everyone but for the right patient, it could be a really interesting experience.”

Other patients have actually picked up and felt their own old heart. But Justin and his family members opted to simply observe from a few feet away, watching others pass it around.

“It was so bizarre to see his heart sitting there in the middle of the table with him standing right next to it,” says his mother, Margaret. “Here was this thing inside his body that almost killed him — and we were looking at it in person.”

Justin had never had any health issues until last summer when he noticed shortness of breath laying down, frequent sluggishness and a loss of appetite. He already needed a physical exam before the start of the school year, so Justin’s mother asked his doctor to move it up.

His mother guessed that maybe he had an iron deficiency or was simply overtired from his outdoor manual labor work. But results of an electrocardiogram concerned his pediatrician, who referred the Romulus, Michigan, family to Mott.

Several more tests over the next few days confirmed shocking news. Justin had developed dilated cardiomyopathy, a condition in which the heart’s muscle cells are abnormal or damaged, limiting the organ’s ability to pump blood.

Justin’s heart was enlarged from inflammation and only pumping a quarter of the amount of blood and oxygen required. Extensive scarring from what appeared to be a virus had caused so much damage it was beyond repair.

There was only one solution — a new heart.

“It was such a whirlwind,” Margaret says. “I still can’t wrap my head around how we went from having this healthy, active boy to suddenly needing a heart transplant for him to live.”

Justin spent some time in the pediatric intensive care unit at Mott but was sent home with medication to keep his blood and oxygen flow healthy. Three weeks later, the family got the highly anticipated call — he had a heart.

Justin only had one question when he awoke from transplant surgery.

“Did you take a picture of my heart?” he asked.

When the answer was no, doctors instead promised to look into whether he could have an in-person introduction.

“The clinicians approached me and said, ‘This may sound like an odd question, but could we let the patient see his heart?’ I said, ‘Sure, why not?’” says Raja Rabah, MD, director of pediatric and perinatal pathology at Mott.

Rabah had been involved with pathology reports on Justin’s heart from the beginning of his care at Mott but had never actually met the patient.

“Pathologists are usually behind the scenes, so it was quite the experience to meet the patient in person,” she says. “We always aim to offer patient-centered care and this definitely helps patients be closer to the process involving their care."

“This has typically been a learning opportunity for clinicians, fellows and the rest of our teams, but we are seeing that it could also be educational for our patients,” she adds.

“We’d like to offer more families the chance to join these conferences to help them better understand the disease affecting them or their loved ones.”

Justin Prybyla with his mother, Margaret and sister, Nicole.Today, Justin is back to his regular self, enjoying previous activities such as bowling. In the spring, he will be taking his first trip post-transplant, traveling to Florida with his mother, sister Nicole and friends from his senior class.

Justin Prybyla with his mother, Margaret and sister, Nicole.Today, Justin is back to his regular self, enjoying previous activities such as bowling. In the spring, he will be taking his first trip post-transplant, traveling to Florida with his mother, sister Nicole and friends from his senior class.

Doctors say the surgery went well and they expect Justin’s new heart to keep him healthy for many years to come.

Meanwhile, the unexpected gift has brought gratitude and perspective.

“Organ donation wasn’t anything I ever thought about before. You never think it’s going to happen to you ... and I didn’t know there were so many kids in the hospital waiting for one,” he says. “In the hospital I kept wishing I could go back a couple of months when I was healthy.

“Right now, I feel normal and get to do regular things. You take feeling normal for granted.”

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Breast team reviewing a patient's slide. (From left to right) Ghassan Allo, Fellow; Laura Walters, Clinical Lecturer; Celina Kleer, Professor. See Article 2014Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Autopsy Technician draws blood while working in the Wayne County morgue. See Article 2016Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD and Postdoctoral Fellow, Chan Chung, PhD investigate pediatric brain cancer. See Article 2017Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Director of the Neuropathology Fellowship, Dr. Sandra Camelo-Piragua serves on the Patient and Family Advisory Council. 2018Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Residents Ashley Bradt (left) and William Perry work at a multi-headed scope in our new facility. 2019Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Kristine Konopka (right) instructing residents while using a multi-headed microscope. 2020Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Patient specimens poised for COVID-19 PCR testing. 2021Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Pantanowitz demonstrates using machine learning in analyzing slides. 2022Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

(Left to Right) Drs. Angela Wu, Laura Lamps, and Maria Westerhoff. 2023Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

MLabs, established in 1985, functions as a portal to provide pathologists, hospitals. and other reference laboratories access to the faculty, staff and laboratories of the University of Michigan Health System’s Department of Pathology. MLabs is a recognized leader for advanced molecular diagnostic testing, helpful consultants and exceptional customer service.