Fear of making a mistake often paralyzes young people as they consider career goals. However, as Dr. Catherine Ptaschinski demonstrates, it is ok to change your mind. Her small, rural high school did not provide many advanced placement courses, and none in the sciences, so her science exposure was limited. She thought she would go into piano performance for a career. When she went to college, however, she thought maybe a career in Public Health would be a better fit, so she pursued Spanish and molecular biology. During her undergrad, she did an honors thesis in molecular biology. “I really, really enjoyed doing that research,” she recalled.

Fear of making a mistake often paralyzes young people as they consider career goals. However, as Dr. Catherine Ptaschinski demonstrates, it is ok to change your mind. Her small, rural high school did not provide many advanced placement courses, and none in the sciences, so her science exposure was limited. She thought she would go into piano performance for a career. When she went to college, however, she thought maybe a career in Public Health would be a better fit, so she pursued Spanish and molecular biology. During her undergrad, she did an honors thesis in molecular biology. “I really, really enjoyed doing that research,” she recalled.

After graduation, she began working in a public health department in Oregon. Soon, she realized this was not where she belonged. She applied for a PhD program in microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York at Syracuse and completed her thesis work in the Rosemary Rochford laboratory. “My thesis project was focused on early-life Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. In the United States, most of us get the EBV later in life. It is the virus that causes mono,” explained Ptaschinski. “However, in much of the world, infection happens very early in life, usually during weaning. EBV is passed through saliva, and parents pre-chew their food and feed it to their infants during weaning because they don’t have baby food.” These infants become infected with EBV. In regions of the world where malaria transmission takes place year-round, these children often develop Burkitt’s lymphoma. “My work in the laboratory explored the interaction of these two pathogens that lead specifically to childhood lymphoma. This research made me very interested in how viruses can impact people differently at different ages. While working on my thesis, I did a lot of background reading, and one of the main viruses that has very age-based different impacts is the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). Young children infected with RSV can become very ill, requiring hospitalization. Many of these will develop childhood asthma and wheezing. After age five, infection risk goes down. I became interested in how and why.”

Ptaschinski had completed a study abroad in Spain during her undergraduate Spanish degree, and wanted a chance to live overseas again. Her postdoctoral fellowship seemed like a good opportunity to do that. One of her thesis advisors suggested the laboratory of Dr. Paul Foster at the University of Newcastle in Australia. “I was there for three years. The lab had an ocean view overlooking a popular surfing beach. We kept a pair of binoculars in the office where we would watch dolphins and whales from our office window. We were very spoiled.” She found that working in an island nation and the United States was quite different. “In the United States, I could order supplies and typically get them overnight. I had to become very good at planning my experiments in Australia, as supplies often take two to four weeks to arrive. That experience forced me to learn to plan my experiments carefully, and that has made a big difference for me.”

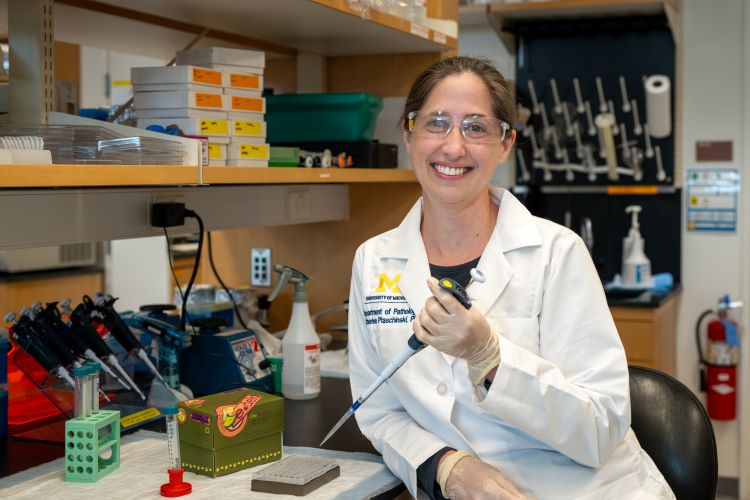

While in the Foster laboratory, Ptaschinski focused on studying RSV in juvenile models. RSV is not limited to just a single type of cell, it causes a systemic immune response, so it was technically very challenging work. “I learned a lot of great techniques and developed some good collaborations in that lab.”

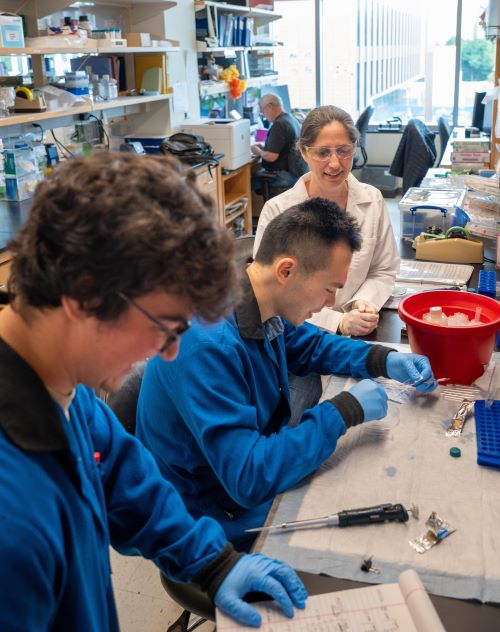

Once she completed her postdoctoral fellowship, she returned to the United States and joined the laboratory of Dr. Nicholas Lukacs, Godfrey Dorr Stobbe professor of pathology and scientific director of the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center at the University of Michigan. Ptaschinski had an opportunity to meet Lukacs when he presented at another laboratory in Australia. Then, during one of her trips to visit her family in Wisconsin, Ptaschinski made a stop at the University of Michigan to meet Lukacs at his laboratory. “At the time, his lab was pretty big, so there were a lot of postdocs, PhD students, and other people working in the lab. I joined his lab as a postdoctoral fellow. We were able to bounce ideas off each other, which was very helpful. We had people with different backgrounds and different areas of expertise who could integrate into our work.” Ptachinski continued her studies on neonatal RSV infection, specifically looking at how the maternal microbiome affects their offspring. Researchers at Henry Ford had been looking at how the bacterial composition of women in houses that had indoor/outdoor pets were much different than those who did not. Children born into homes with indoor/outdoor pets experienced a lower incidence of allergies. Ptaschinski applied this finding to her RSV research. “When the mothers had this microbiome during pregnancy, it was very protective for early life RSV infection. We did not see any of the pathology normally associated with early RSV infections.”

Once she completed her postdoctoral fellowship, she returned to the United States and joined the laboratory of Dr. Nicholas Lukacs, Godfrey Dorr Stobbe professor of pathology and scientific director of the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center at the University of Michigan. Ptaschinski had an opportunity to meet Lukacs when he presented at another laboratory in Australia. Then, during one of her trips to visit her family in Wisconsin, Ptaschinski made a stop at the University of Michigan to meet Lukacs at his laboratory. “At the time, his lab was pretty big, so there were a lot of postdocs, PhD students, and other people working in the lab. I joined his lab as a postdoctoral fellow. We were able to bounce ideas off each other, which was very helpful. We had people with different backgrounds and different areas of expertise who could integrate into our work.” Ptachinski continued her studies on neonatal RSV infection, specifically looking at how the maternal microbiome affects their offspring. Researchers at Henry Ford had been looking at how the bacterial composition of women in houses that had indoor/outdoor pets were much different than those who did not. Children born into homes with indoor/outdoor pets experienced a lower incidence of allergies. Ptaschinski applied this finding to her RSV research. “When the mothers had this microbiome during pregnancy, it was very protective for early life RSV infection. We did not see any of the pathology normally associated with early RSV infections.”

This work led Ptaschinski to focus more on asthma and food allergies. “This seems like a big jump moving from lungs to intestines, but the mucosal immune system in both sites is quite similar, with many similar mechanisms at play.” Since most food allergies develop early in life, this seemed like a natural progression. “My work right now is focused on barrier function in food allergy. The mucosal lining of the intestine is a single cell layer separating the food side from the immune system. Several different protein complexes keep the barrier nice and robust, allowing nutrients and water to go through, but not bacteria or other harmful agents.” Food particles can pass through and encounter the immune system when this barrier is disrupted. “Allergies are an overreaction of the immune system to something that should be harmless. Does a disruption of the barrier contribute to developing food allergies?”

Ptaschinski also noted that there is a strong link between eczema during infancy and the development of food allergies. “Is there something in the skin causing a reaction in the intestine? Is this just somebody who is more likely to be allergic to things? We are investigating whether there is an actual immune communication between those two sites in terms of different barrier functions.” In addition, she is looking specifically at a protein called the junctional adhesion molecule A, or Jam-A. “This protein controls the permeability of the intestinal epithelial barrier. It can change that barrier to let bigger or smaller things pass through. This has been known for a long time. But it is also highly expressed in the skin, and no one has looked at whether it’s associated with allergic disease. So, we have a lot of genetic tools that we are using to investigate this.”

Ptaschinski also noted that there is a strong link between eczema during infancy and the development of food allergies. “Is there something in the skin causing a reaction in the intestine? Is this just somebody who is more likely to be allergic to things? We are investigating whether there is an actual immune communication between those two sites in terms of different barrier functions.” In addition, she is looking specifically at a protein called the junctional adhesion molecule A, or Jam-A. “This protein controls the permeability of the intestinal epithelial barrier. It can change that barrier to let bigger or smaller things pass through. This has been known for a long time. But it is also highly expressed in the skin, and no one has looked at whether it’s associated with allergic disease. So, we have a lot of genetic tools that we are using to investigate this.”

Ptaschinski aims to understand how immune activation occurs and which cells are involved. From there, she hopes to discover a means to block those particular immune cells to prevent allergic responses. “We have found that if we can attach an antibody that blocks mast cells from accumulating in the intestine, we don’t get an allergic response. Now we are investigating genetic and environmental factors that impact barrier function.”

As a researcher, Ptaschinski revels in the times when she makes a discovery and, for that brief moment, is the only person who knows that thing. “It is a real privilege and is very exciting. And now I can share that with trainees and go through that process with students and postdoctoral fellows – watching them experience that discovery process.” She added, “The point of science is not understanding what is happening. Until I understood that, I hated science. Then, I just fell in love with it.” When undergrads first come into her laboratory, they often ask what the expected outcome is as they set up an experiment. “I tell them, ‘I don’t know,’ and that is often a real light-bulb moment for them. They get very excited about that. It is really fun to see.”

Outside the lab, she enjoys hiking with her dog, growing hot peppers, and knitting socks. “Just regular socks, not slippers. I like knitting in general, but with socks, once you get it started, you are just knitting in circles. It gives me something to do with my hands while watching a movie. The worst part about summer is I can’t wear my wool socks – it is too hot!”

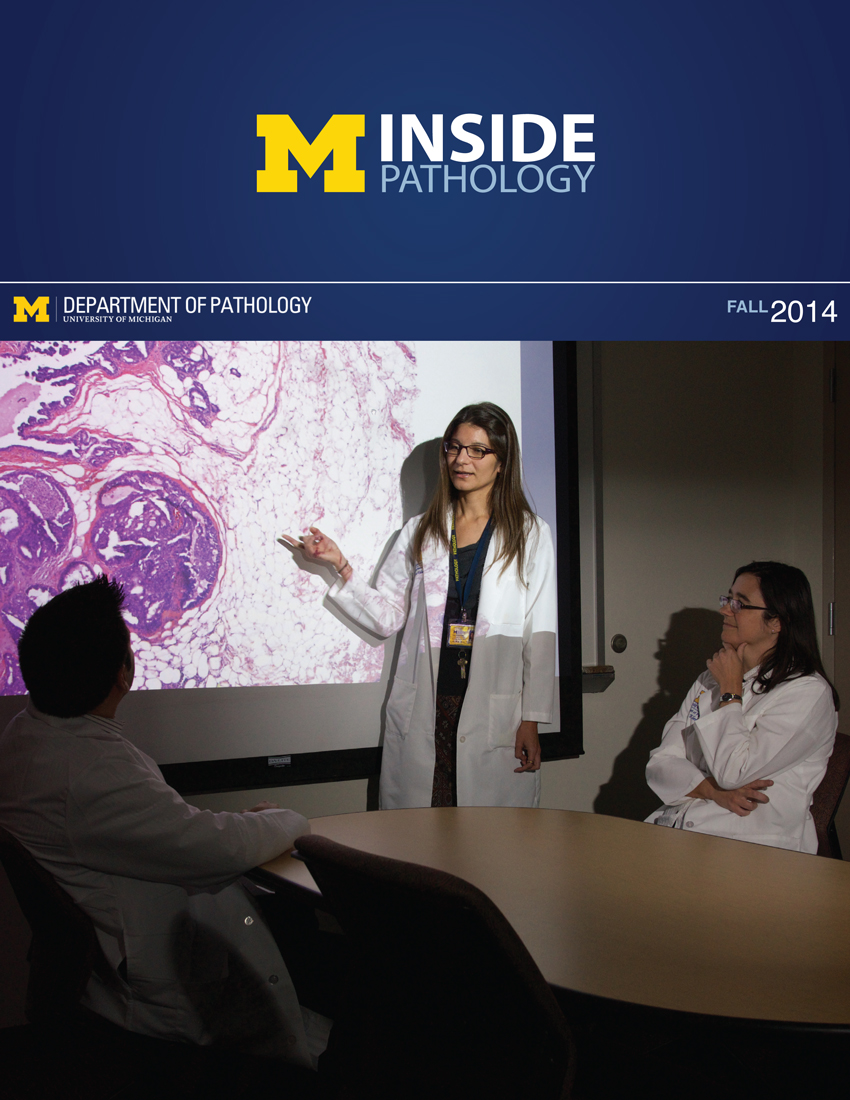

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Breast team reviewing a patient's slide. (From left to right) Ghassan Allo, Fellow; Laura Walters, Clinical Lecturer; Celina Kleer, Professor. See Article 2014Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Autopsy Technician draws blood while working in the Wayne County morgue. See Article 2016Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD and Postdoctoral Fellow, Chan Chung, PhD investigate pediatric brain cancer. See Article 2017Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Director of the Neuropathology Fellowship, Dr. Sandra Camelo-Piragua serves on the Patient and Family Advisory Council. 2018Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Residents Ashley Bradt (left) and William Perry work at a multi-headed scope in our new facility. 2019Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Kristine Konopka (right) instructing residents while using a multi-headed microscope. 2020Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Patient specimens poised for COVID-19 PCR testing. 2021Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

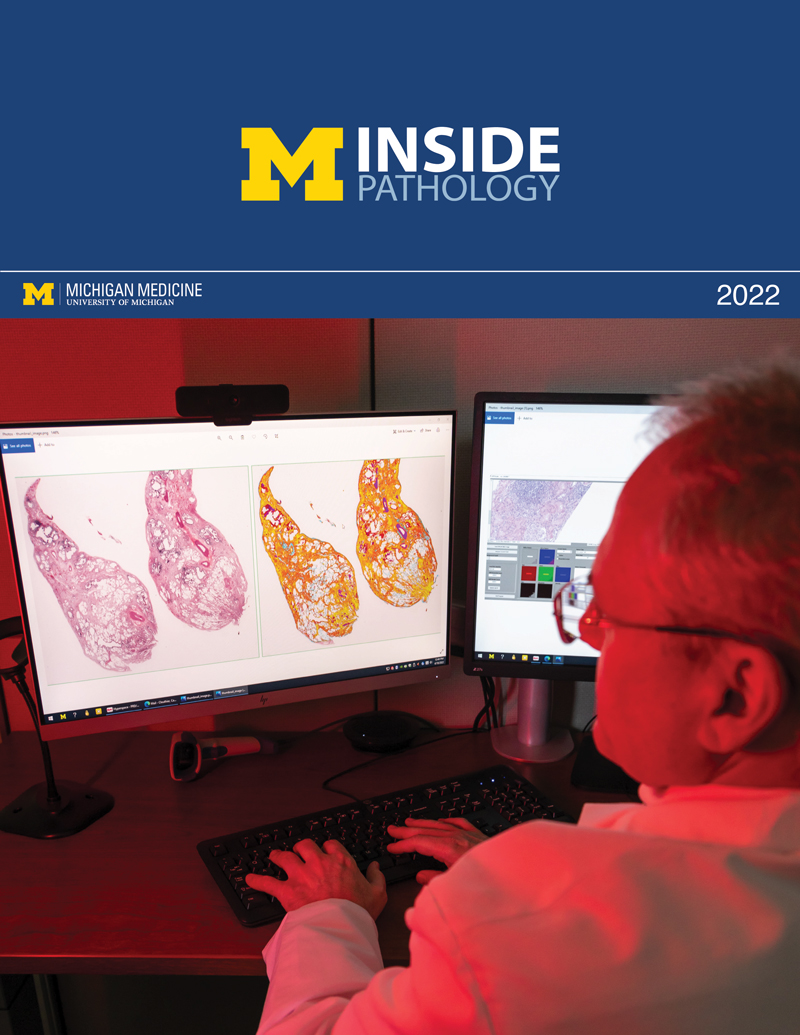

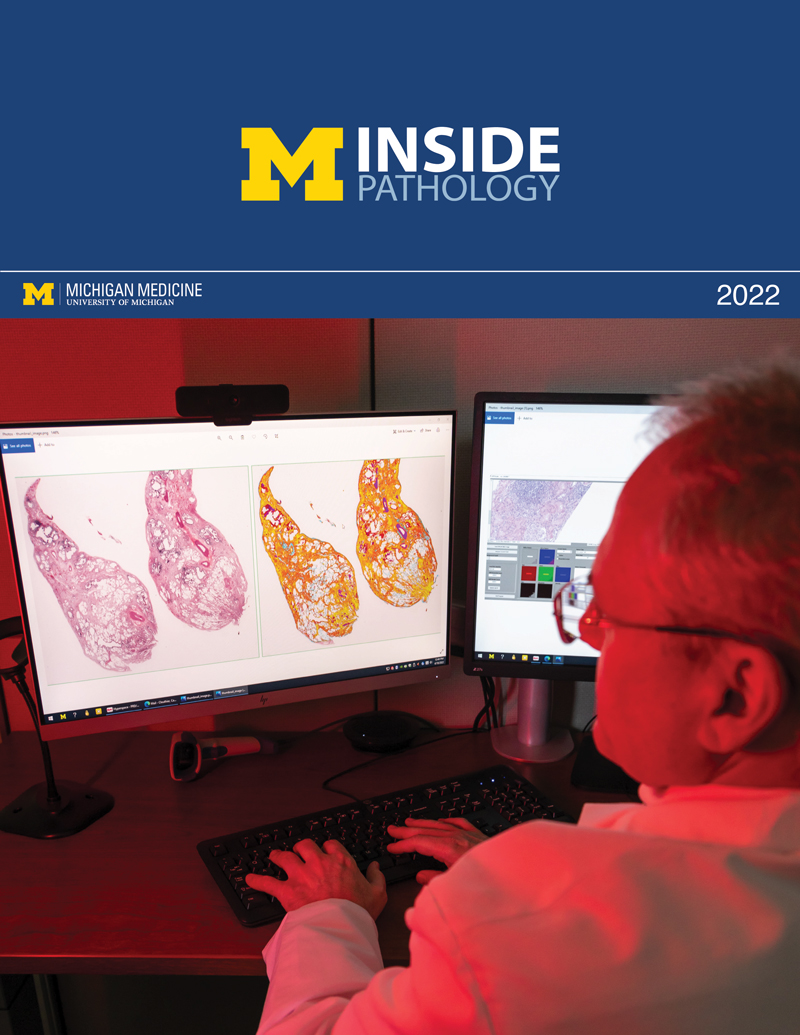

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Pantanowitz demonstrates using machine learning in analyzing slides. 2022Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

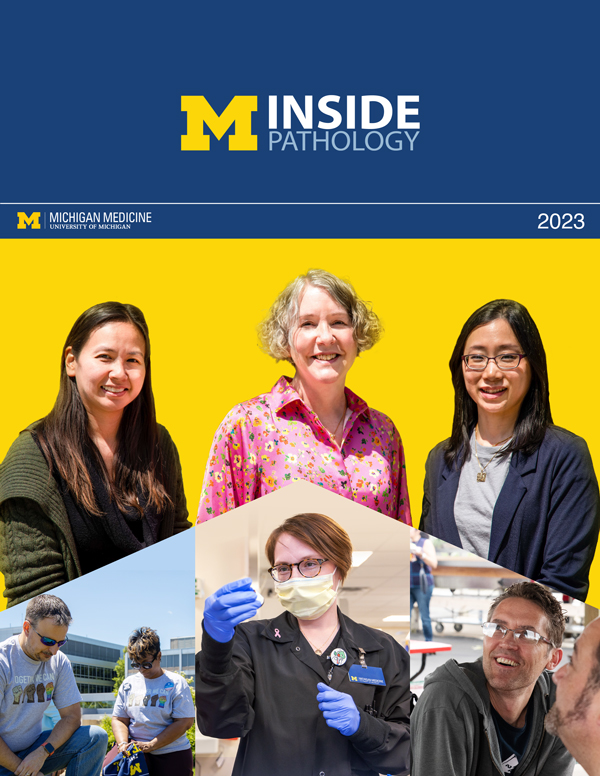

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

(Left to Right) Drs. Angela Wu, Laura Lamps, and Maria Westerhoff. 2023Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Illustration representing the various machines and processing used within our labs. 2024Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

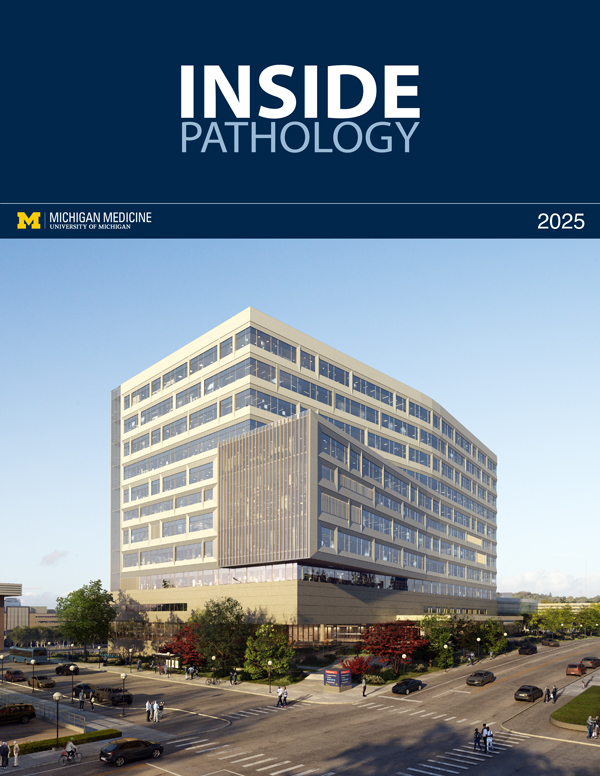

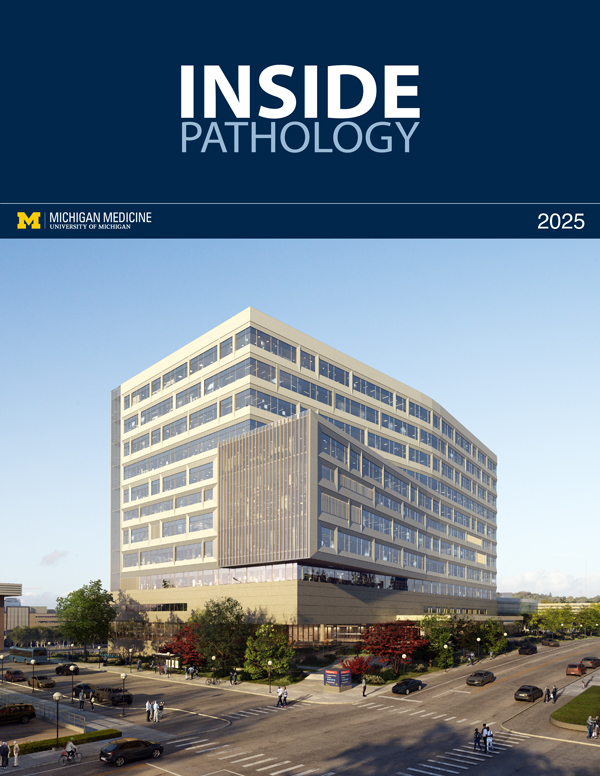

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Rendering of the D. Dan and Betty Khn Health Care Pavilion. Credit: HOK 2025Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

MLabs, established in 1985, functions as a portal to provide pathologists, hospitals. and other reference laboratories access to the faculty, staff and laboratories of the University of Michigan Health System’s Department of Pathology. MLabs is a recognized leader for advanced molecular diagnostic testing, helpful consultants and exceptional customer service.