.png)

.png)

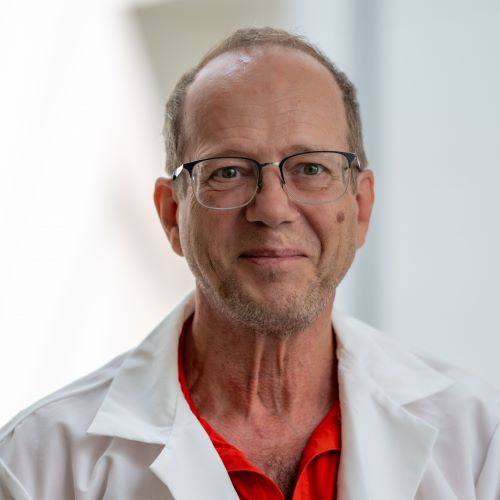

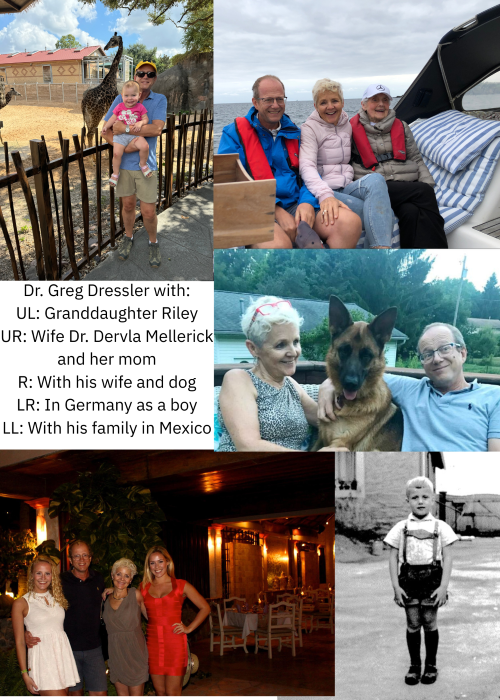

In 1967, an 8-year-old German boy stepped off a boat onto American soil for the first time. His father, an engineer, had been recruited to work in America, but little Greg knew no English and wondered what this new life in America would hold for him and his family. A few days later, he walked into his new school room as a second-grade student and struggled to learn the English language and culture as he continued his education. These humble beginnings helped shape the man who went on to pursue a long, successful research career at the University of Michigan, Dr. Greg Dressler, emeritus professor and Collegiate Professor of Pathology Research.

In 1967, an 8-year-old German boy stepped off a boat onto American soil for the first time. His father, an engineer, had been recruited to work in America, but little Greg knew no English and wondered what this new life in America would hold for him and his family. A few days later, he walked into his new school room as a second-grade student and struggled to learn the English language and culture as he continued his education. These humble beginnings helped shape the man who went on to pursue a long, successful research career at the University of Michigan, Dr. Greg Dressler, emeritus professor and Collegiate Professor of Pathology Research.

Dressler loved to solve puzzles and inherited his father's enjoyment of craftwork. He decided to attend the University of Pennsylvania to pursue an undergraduate education in engineering, with a focus on chemical and bioengineering, a new field at the time. “I got into the organic chemistry lab, and I loved it!” exclaimed Dressler. “I was able to create things with my hands and solve problems.” After graduation, Dressler worked as a lab tech in the Wistar Institute’s virology lab. “This lab was on the U-Penn campus, but it is a private lab founded by Casper Wistar in the 1790s.” Here, he learned to sequence DNA in human brain tissue. “This was cutting edge in 1981. It was only 4 or 5 years since the discovery of recombinant DNA. It was exciting research.”

As a result of his experience in the Wistar lab, Dressler decided to pursue a PhD in Genetics from the University of Pennsylvania, while continuing to work in the virology lab. It was at this time he met his wife, Dr. Dervla Mellerick. Upon completion of his PhD in 1986, Dressler returned to Germany to complete his postdoctoral fellowship at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry as The Alexander von Humboldt Fellow in the Peter Gruss lab. “In this lab, we were researching mammalian genes. Viral genetics is much simpler. It was in the Gruss lab that I began getting interested in the kidney, and we discovered the Pax gene family and characterized the Pax2 gene in the developing kidney and nervous system.” After three years, Dressler returned to the United States and worked as a senior staff fellow at the NIH Unit on Molecular Embryology, Laboratory of Mammalian Genes and Development in the National Institute of Chronic Health Diseases in Bethesda, MD, where he continued his work on Pax2. He demonstrated that Pax 2 was expressed in renal progenitor cells, renal carcinoma, and Wilms’ tumor, but not in normal adult proximal tubules. He used genetic and molecular biochemistry approaches to show that deregulation of Pax2 led to severe kidney abnormalities. “Today, scientists can sequence an entire genome. When these discoveries were made, 20-30 years ago, we used genetic studies to verify and define gene function, one gene at a time. We used animal models and characterized function based on phenotype. Mice that lack the Pax2 gene don’t develop kidneys during embryonic development. It was pretty clear that Pax2 was an important gene.” Research was conducted using yeast, flies, fish, and mice looking for markers of phenotypes – what the mutations caused. “It was the golden age of recombinant DNA and cloning. It enabled people to sequence genomes. It was exciting to be on the cutting edge of research. Today, entire genomes are sequenced, and computational analysis on big data is required. Labs need people who understand coding, bioinformatics, and computational biology. Research requires a lot more people than it did when I started.”

In 1994, Dr. David Humes, a physician-scientist at Michigan in Nephrology, invited Dressler for a seminar presentation. “The Department of Pathology, under Dr. Peter Ward, showed interest and invited me to join their faculty as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Assistant Investigator. I liked the community of Ann Arbor better than the congestion of Bethesda, and the University of Michigan was home to a robust research community, so we decided to come.” Dressler continued his research, demonstrating that glial-cell derived neurotrophic factor was the ligand for the c-ret tyrosine kinase and promoted renal epithelial cell migration in the developing kidney. Over the next three years, he sailed through the ranks to full professor in 1997. In 2007, he received the Dean’s Basic Science Award and was named the Collegiate Professor of Pathology Research in 2008, an honor he currently holds.

In 1994, Dr. David Humes, a physician-scientist at Michigan in Nephrology, invited Dressler for a seminar presentation. “The Department of Pathology, under Dr. Peter Ward, showed interest and invited me to join their faculty as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Assistant Investigator. I liked the community of Ann Arbor better than the congestion of Bethesda, and the University of Michigan was home to a robust research community, so we decided to come.” Dressler continued his research, demonstrating that glial-cell derived neurotrophic factor was the ligand for the c-ret tyrosine kinase and promoted renal epithelial cell migration in the developing kidney. Over the next three years, he sailed through the ranks to full professor in 1997. In 2007, he received the Dean’s Basic Science Award and was named the Collegiate Professor of Pathology Research in 2008, an honor he currently holds.

His lab went on to discover the first secreted enhancer of BMP signaling called Kielin/Chordin-like Protein (KCP), demonstrating its important role in mediating fibrotic disease in the kidney and liver. He also discovered an adaptor protein that links the Pax family of DNA-binding proteins to the MLL family of histone H4, lysine 4 methyltransferases called PTIP. This work defined a new paradigm for how developmental regulatory proteins can imprint cell lineage specificity through epigenetic modification of the genome. These are just a few of his many discoveries, which he published in 123 peer-reviewed papers and 19 book chapters over his career.

Dressler is now entering retirement. “I am cleaning out my lab now. It is kind of sad to see work thrown out that I’ve spent my life on.” But he is not completely done. He continues to support Drs. Jeff Beamish, assistant professor of nephrology, and Abdul Soofi, research assistant professor of internal medicine, as they finish up joint projects and publish results. “I will still be writing manuscripts for publication for another two or three years,” said Dressler. Looking back over his career, Dressler really enjoyed being able to help others with writing grants and manuscripts. “I had excellent writing instructors going all the way back to high school. In fact, my high school writing teacher was the mother of a Pulitzer-winning fictional writer. She taught us both how to write.” Another fond memory was being called as an expert witness for a legal case. “The case revolved around Pax 2, the gene that I discovered. I was the world’s foremost expert on this gene. It paid quite well, but I don’t expect that will ever be repeated.”

Something that Dressler learned over the years that he hopes upcoming researchers understand is that nearly everyone suffers from impostor syndrome. “A lot of very smart people doubt themselves all the time. They don’t feel like they fit in. Some of the most accomplished people have impostor syndrome. Those who are overly confident are often less accomplished. Forming relationships in research takes time to build trust, so people will let down their guard and let you get past insecurities.”

Something that Dressler learned over the years that he hopes upcoming researchers understand is that nearly everyone suffers from impostor syndrome. “A lot of very smart people doubt themselves all the time. They don’t feel like they fit in. Some of the most accomplished people have impostor syndrome. Those who are overly confident are often less accomplished. Forming relationships in research takes time to build trust, so people will let down their guard and let you get past insecurities.”

As he enters retirement, Dressler is looking forward to spending more time with his wife, two daughters, and his 2-year-old granddaughter. He is eager to ski the mountains of Utah when he visits his daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter in Salt Lake City. His other daughter is local, and he will enjoy having more time to spend with her and her husband. He anticipates his life will be filled with walks with his wife, going to shows in New York, playing golf and duplicate bridge, music (he loves emotional music such as opera, classical, jazz, and the blues), taking road trips with the top down on his Mercedes on a sunny day, and taking his dog for a walk. Just simple things that add up to a life filled with joy and contentment.

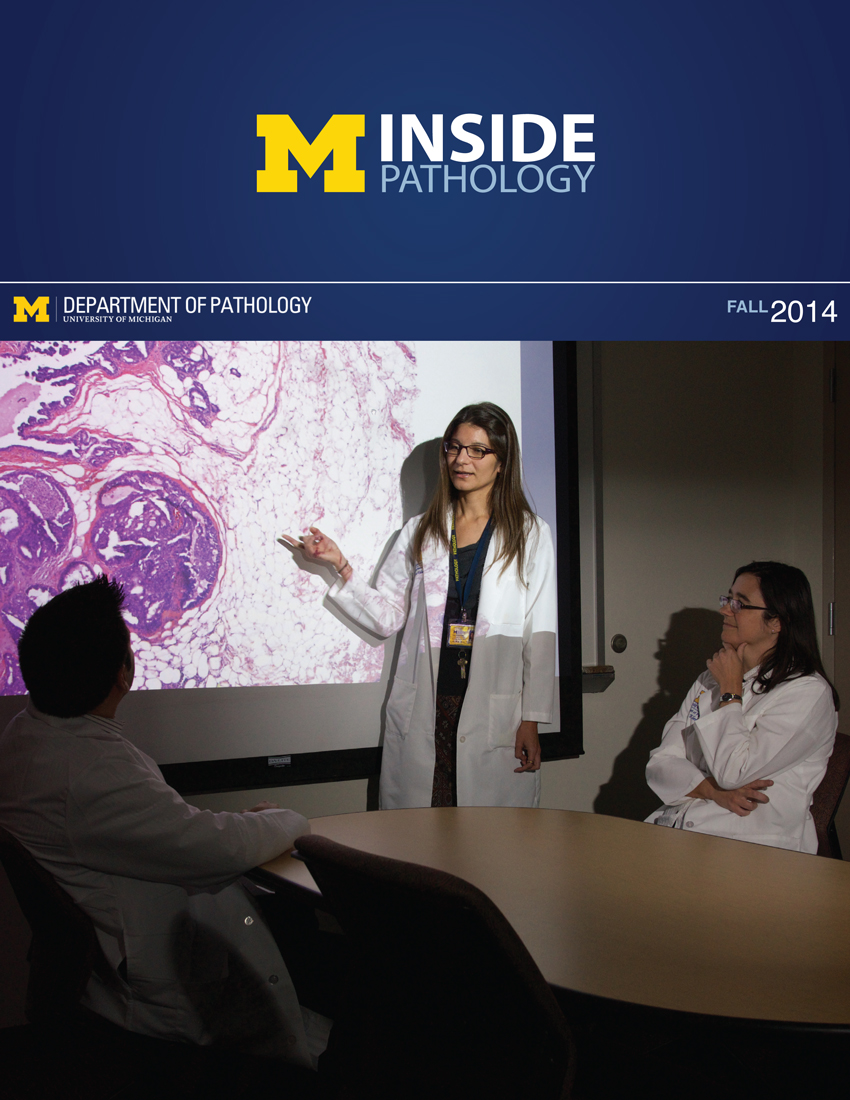

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Breast team reviewing a patient's slide. (From left to right) Ghassan Allo, Fellow; Laura Walters, Clinical Lecturer; Celina Kleer, Professor. See Article 2014Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Autopsy Technician draws blood while working in the Wayne County morgue. See Article 2016Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD and Postdoctoral Fellow, Chan Chung, PhD investigate pediatric brain cancer. See Article 2017Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Director of the Neuropathology Fellowship, Dr. Sandra Camelo-Piragua serves on the Patient and Family Advisory Council. 2018Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Residents Ashley Bradt (left) and William Perry work at a multi-headed scope in our new facility. 2019Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Kristine Konopka (right) instructing residents while using a multi-headed microscope. 2020Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Patient specimens poised for COVID-19 PCR testing. 2021Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

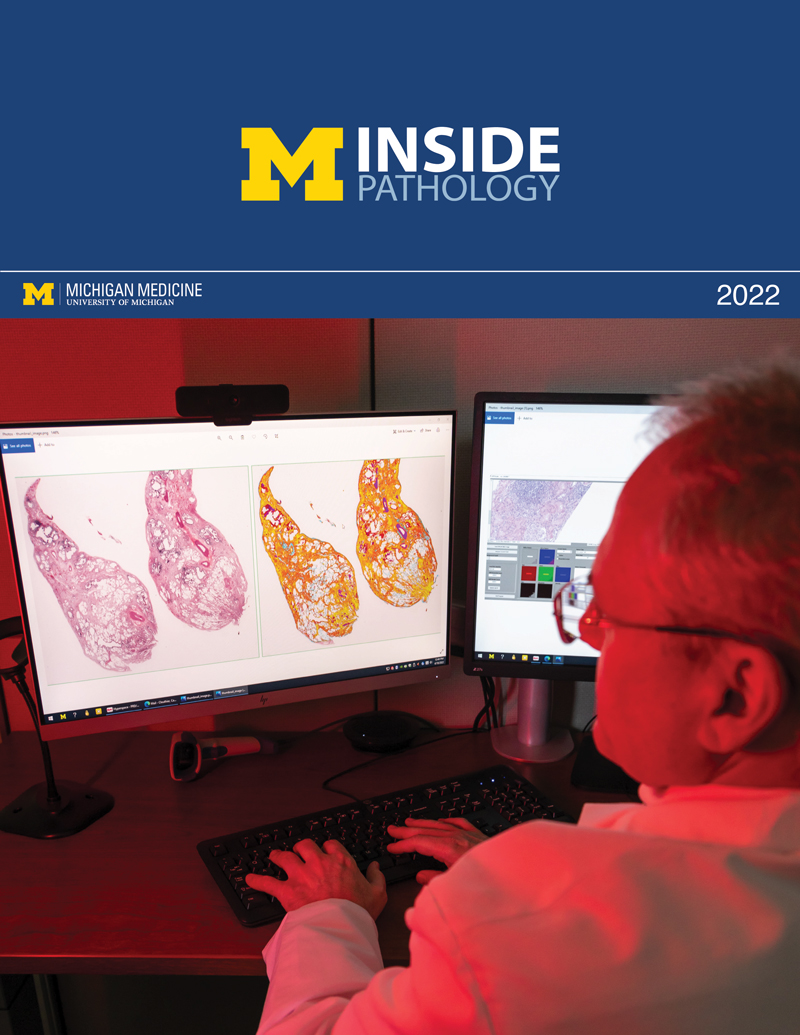

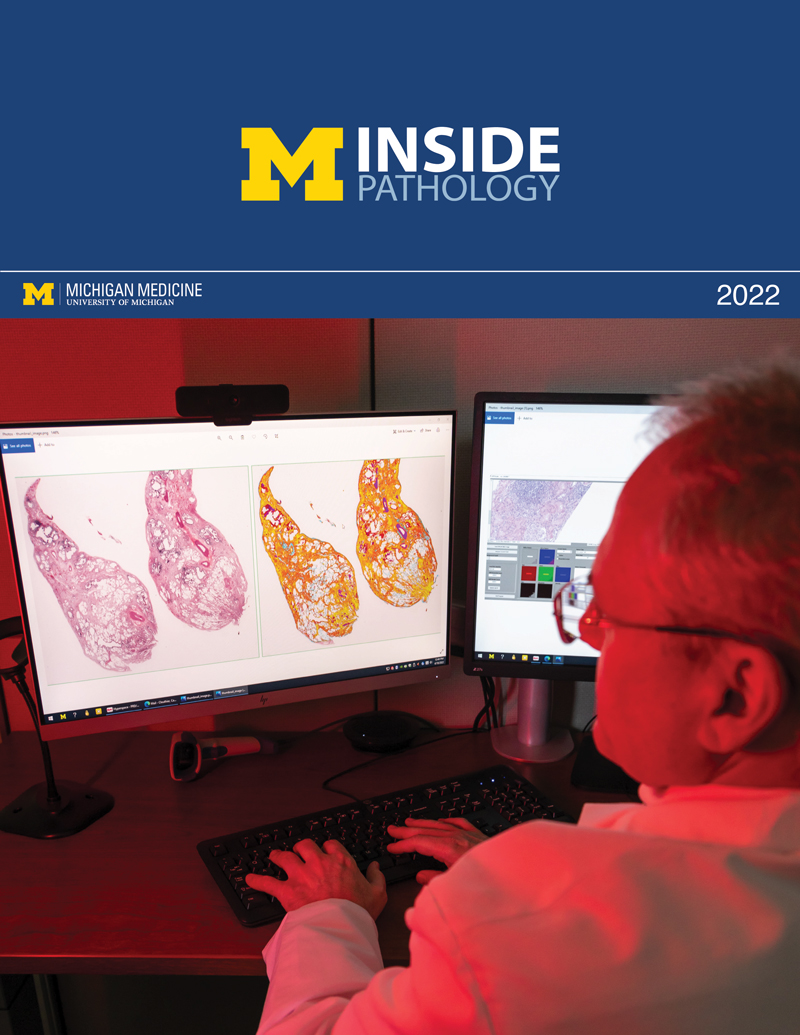

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Pantanowitz demonstrates using machine learning in analyzing slides. 2022Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

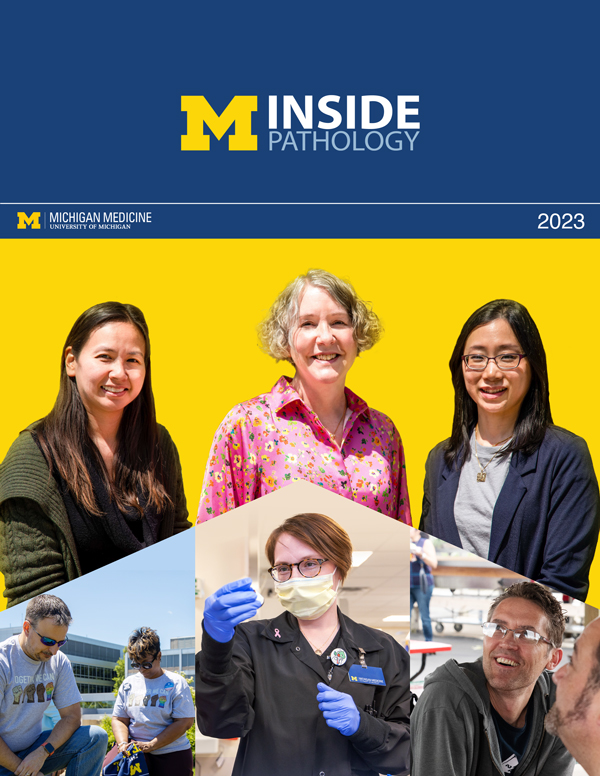

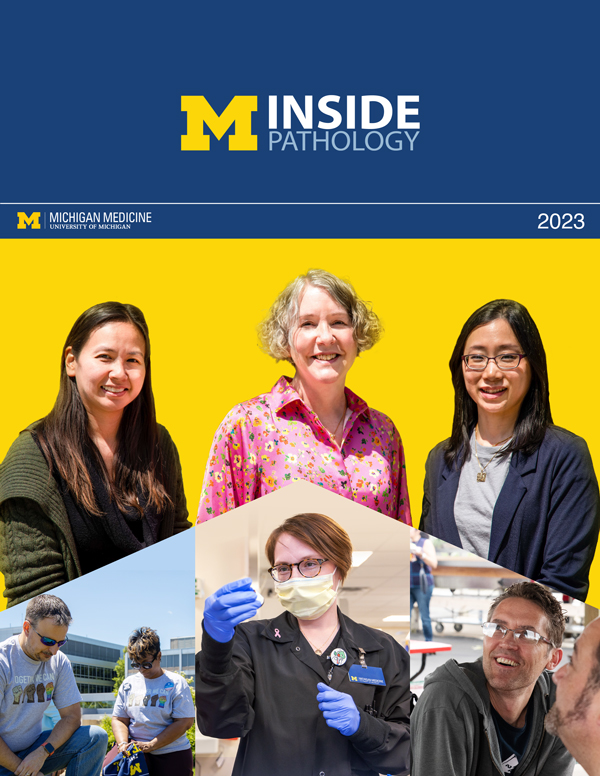

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

(Left to Right) Drs. Angela Wu, Laura Lamps, and Maria Westerhoff. 2023Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Illustration representing the various machines and processing used within our labs. 2024Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Rendering of the D. Dan and Betty Khn Health Care Pavilion. Credit: HOK 2025Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

MLabs, established in 1985, functions as a portal to provide pathologists, hospitals. and other reference laboratories access to the faculty, staff and laboratories of the University of Michigan Health System’s Department of Pathology. MLabs is a recognized leader for advanced molecular diagnostic testing, helpful consultants and exceptional customer service.