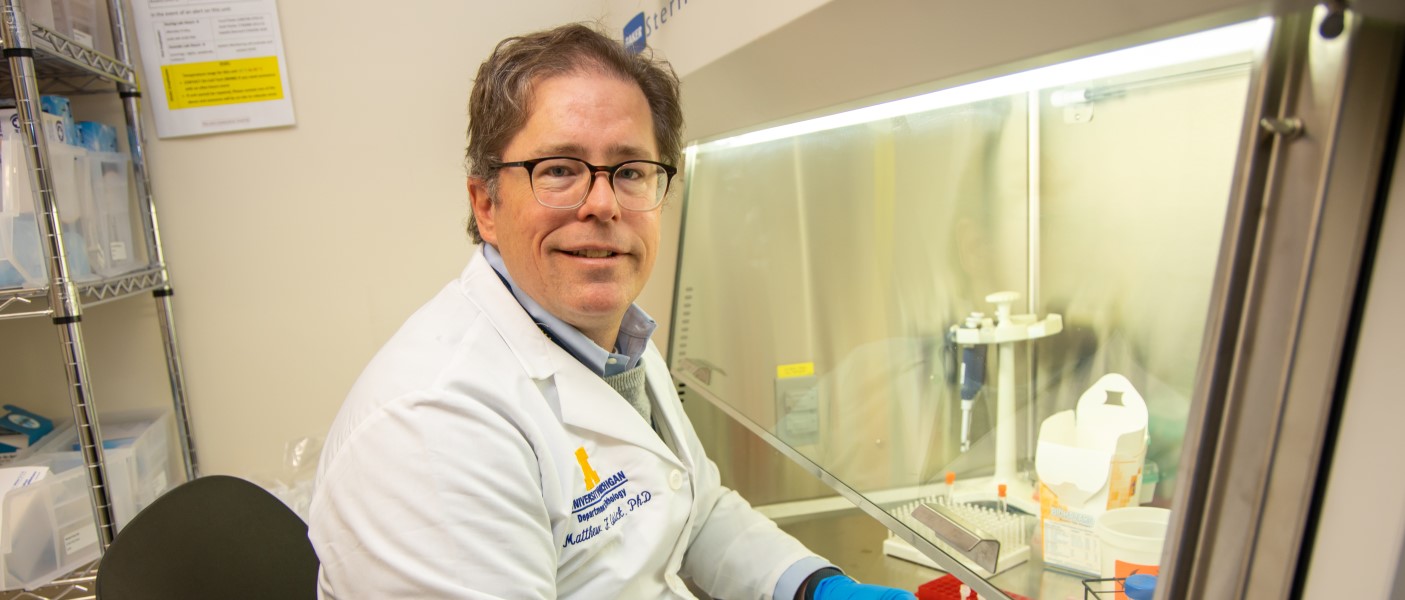

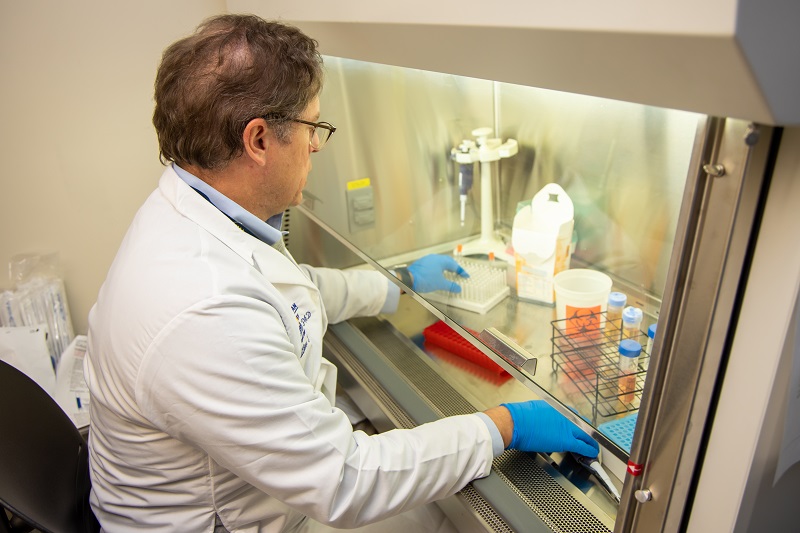

Born and raised in Elm Grove, Wisconsin, a suburb of Milwaukee, Matthew “Matt” Cusick, moved across country several times before settling back in the Midwest for his career. First, he moved to Omaha, Nebraska where he attended Creighton University for his undergraduate program, followed by a cross-country move to the University of Vermont for graduate school, then back west to the University of Utah, preceded by a brief stop in Wisconsin, where he completed his PhD and Postdoctoral Fellowship. “I like to downhill ski,” explained Cusick. “It kind of drove my life for a long time, determining where I would live. If there were mountains, I veered toward them.” However, skiing wasn’t the only priority in life, and by 2017, Cusick had accepted an Assistant Professor of Surgery position at Baylor University in Texas, where he led the HLA laboratory. In 2019, he was recruited to Michigan Medicine as the Director of the HLA Laboratory and Assistant Professor of Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics in the Department of Pathology.

Born and raised in Elm Grove, Wisconsin, a suburb of Milwaukee, Matthew “Matt” Cusick, moved across country several times before settling back in the Midwest for his career. First, he moved to Omaha, Nebraska where he attended Creighton University for his undergraduate program, followed by a cross-country move to the University of Vermont for graduate school, then back west to the University of Utah, preceded by a brief stop in Wisconsin, where he completed his PhD and Postdoctoral Fellowship. “I like to downhill ski,” explained Cusick. “It kind of drove my life for a long time, determining where I would live. If there were mountains, I veered toward them.” However, skiing wasn’t the only priority in life, and by 2017, Cusick had accepted an Assistant Professor of Surgery position at Baylor University in Texas, where he led the HLA laboratory. In 2019, he was recruited to Michigan Medicine as the Director of the HLA Laboratory and Assistant Professor of Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics in the Department of Pathology.

“I sort of fell into HLA as a career,” stated Cusick. “HLA stands for human leukocyte antigen. I was interested in immunology and I met Dr. David Eckels, who did viral immunology research. He was also the director of an HLA laboratory in Milwaukee.” When Eckels relocated to Utah, Cusick followed him and completed his PhD in Experimental Pathology. “He gave me this unbelievable opportunity. I had to earn it, but he allowed me the space to fail. He let me figure it out on my own. He believed that if you could not figure it out, it is better to know sooner rather than later. It was tough love, but it was great.”

The human leukocyte antigen, “HLA, is one of the most polymorphic regions of the human genome. While most parts of the genome are pretty much the same between individuals, this region is quite variable. It controls, or shapes, your memory immune response.” This enables your body to drive an appropriate immune response to clear any pathogens it may encounter. The HLA laboratory conducts testing to determine if cells or organs from a potential donor match those of the intended recipient. If they don’t match, the recipient’s body will mount an immune response to destroy and clear the donor cells or organs from the body. “This region of the genome is also associated with many autoimmune diseases, such as celiac disease or ankylosing spondylitis. In addition to organ transplant testing, we test to determine risk of these diseases,” added Cusick.

When an organ is available for transplantation, the HLA Lab tests to determine which antigens are present in the tissues. These results are compared to those who are awaiting transplant using a national transplant registry. “Transplant committees have to look at who is disadvantaged and give them priority. This is number one. They look at who doesn’t have a common haplotype or genetic background, such as African Americans or women who have been pregnant. African Americans are from the ‘cradle of civilization’ and are very admixed from an HLA perspective. Women who have been pregnant have developed antibodies against paternal antigens. This makes them more difficult to match. We want to be sure those who are disadvantaged have a chance at those rare matches,” Cusick explained. Organ supply is limited and there are a lot of people needing organs. While research is ongoing to find other options, the best option is to increase the donor pool. The more people willing to donate organs, the more likely those awaiting transplant will obtain a good match. Sometimes, less-than-ideal matches are made, “but then you have scenarios where you have too much medication and people become susceptible to other things, such as infections. It is a quality of life and maintenance issue.” One of the burdens of this work for Cusick is that he has seen people on the waitlist die before a match can be found. “I feel it every day. I want to see people get transplanted, and that’s probably the hardest part.” Artificial organs, xenograph transplantations (animal-to-human), and external mechanical devices are primarily bridges to transplantation. Donor organs are still essential for patients to survive.

When an organ is available for transplantation, the HLA Lab tests to determine which antigens are present in the tissues. These results are compared to those who are awaiting transplant using a national transplant registry. “Transplant committees have to look at who is disadvantaged and give them priority. This is number one. They look at who doesn’t have a common haplotype or genetic background, such as African Americans or women who have been pregnant. African Americans are from the ‘cradle of civilization’ and are very admixed from an HLA perspective. Women who have been pregnant have developed antibodies against paternal antigens. This makes them more difficult to match. We want to be sure those who are disadvantaged have a chance at those rare matches,” Cusick explained. Organ supply is limited and there are a lot of people needing organs. While research is ongoing to find other options, the best option is to increase the donor pool. The more people willing to donate organs, the more likely those awaiting transplant will obtain a good match. Sometimes, less-than-ideal matches are made, “but then you have scenarios where you have too much medication and people become susceptible to other things, such as infections. It is a quality of life and maintenance issue.” One of the burdens of this work for Cusick is that he has seen people on the waitlist die before a match can be found. “I feel it every day. I want to see people get transplanted, and that’s probably the hardest part.” Artificial organs, xenograph transplantations (animal-to-human), and external mechanical devices are primarily bridges to transplantation. Donor organs are still essential for patients to survive.

For those who may be interested in a career in HLA, Cusick explained, “HLA is a very niche career. There are probably 200 HLA directors in the nation.” Obtaining a very good understanding of immunology is essential for success in this career. “It isn’t just about the lab work, but you have to have a good understanding of the fundamental principles behind human immunology.” He went on to explain that textbook knowledge is not enough for success in this field. Students need to gain actual hands-on experience as HLA is the definition of precision medicine. Each case, each individual, is unique. Everything is customized to the patient. In addition, “you have to execute well. You work with many different clinical teams that all need something different. Pediatric versus adult immune responses are also different. Heart versus kidney, again, is very different because of the risk and so many other factors. Then bone marrow transplantation is completely the opposite of everything we do for solid organs. You need time to gain experience.”

The biggest challenge for Cusick, however, is the informatics side of the equation; making sure the pipelines and processes make sense within the system and that they evolve appropriately. In addition, there is a severe lack of qualified histotechnologists. “Staffing shortages are a challenge as you need to ensure you maintain the highest quality in patient care, but you also want to stay cutting edge,” he explained. “You can’t do everything you want to do when you are facing staffing shortages.” That being said, he finds great joy in his work. “I love seeing a highly sensitized patient get transplanted and do well, especially if they have been on the list for a long time.”

The biggest challenge for Cusick, however, is the informatics side of the equation; making sure the pipelines and processes make sense within the system and that they evolve appropriately. In addition, there is a severe lack of qualified histotechnologists. “Staffing shortages are a challenge as you need to ensure you maintain the highest quality in patient care, but you also want to stay cutting edge,” he explained. “You can’t do everything you want to do when you are facing staffing shortages.” That being said, he finds great joy in his work. “I love seeing a highly sensitized patient get transplanted and do well, especially if they have been on the list for a long time.”

In addition to his work in the HLA lab, Cusick also sits on numerous transplant committees, providing his expertise to surgeons and others. He also engages in teaching residents and fellows, conducts research, writes manuscripts and engages in ongoing learning. “There are a lot of really great people here. We’ve had some very interesting cases where we’ve been able to talk and I have learned many things, especially from our molecular pathology, hematopathology, and cytogenetics colleagues,” said Cusick. “It benefits patients and can shift the way we think and go about our practices. It can lead to transformation and improvements. I am excited by these opportunities.”

Cusick enjoys the challenge of asking a question, then drilling down to find the answer. He is currently collaborating with others on a study related to COVID-19 susceptibility and HLA. He is also studying the cellular immune responses driving rejections. Examining newer platforms and identifying ways to upgrade the laboratory is another area of research interest. In a recent study, he compared chimerism testing using capillary electrophoresis (CE - standard of care) with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) to determine if NGS could accurately measure the percentage of donor/recipient mixtures in a sample. He found that CE and NGS were significantly correlated and that the NGS method could also help identify suitable donors for solid organ transplant patients using ancestry SNP profiles.

When he is not working, Cusick enjoys time with his wife and two children and his two yellow labs. “We like to go to lakes and do anything outdoors. As I mentioned earlier, I also love to downhill ski!” concluded Cusick.

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Breast team reviewing a patient's slide. (From left to right) Ghassan Allo, Fellow; Laura Walters, Clinical Lecturer; Celina Kleer, Professor. See Article 2014Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Autopsy Technician draws blood while working in the Wayne County morgue. See Article 2016Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD and Postdoctoral Fellow, Chan Chung, PhD investigate pediatric brain cancer. See Article 2017Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Director of the Neuropathology Fellowship, Dr. Sandra Camelo-Piragua serves on the Patient and Family Advisory Council. 2018Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Residents Ashley Bradt (left) and William Perry work at a multi-headed scope in our new facility. 2019Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Kristine Konopka (right) instructing residents while using a multi-headed microscope. 2020Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Patient specimens poised for COVID-19 PCR testing. 2021Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Pantanowitz demonstrates using machine learning in analyzing slides. 2022Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

(Left to Right) Drs. Angela Wu, Laura Lamps, and Maria Westerhoff. 2023Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Illustration representing the various machines and processing used within our labs. 2024Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Rendering of the D. Dan and Betty Khn Health Care Pavilion. Credit: HOK 2025Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

MLabs, established in 1985, functions as a portal to provide pathologists, hospitals. and other reference laboratories access to the faculty, staff and laboratories of the University of Michigan Health System’s Department of Pathology. MLabs is a recognized leader for advanced molecular diagnostic testing, helpful consultants and exceptional customer service.