By Jeffrey Jentzen | 9 May

In the summer of 2007, a UMHS Survival Flight plane, carrying 2 pilots and a 4-member transplant team, crashed into Lake Michigan. The team had procured a set of lungs from a donor in Milwaukee and was headed back to Ann Arbor when the plane went down. At the time, Jeffrey Jentzen had not yet joined the UMHS Department of Pathology. Instead, he was working in Wisconsin as the medical examiner for Milwaukee County. His office was responsible for identifying the Survival Flight bodies. He recalls standing on the beach, the bodies a mile out, and his office without a boat. "We were at the mercy of other agencies to recover the bodies," says Jentzen, who was accustomed to having his own investigators make the recovery. This time he had to wait, an experience he describes as "humbling."

Eventually, the Medical Examiner's Office was able to procure and identify the bodies, which were subsequently released back to their families. Jentzen traveled to UMHS, where he met with those families. "Bodies are an important aspect of the grieving process," he explains. "Having them back is important to the family. The military has a practice where they do not leave bodies on foreign soil. In non-military cases, families also really want their loved ones back."

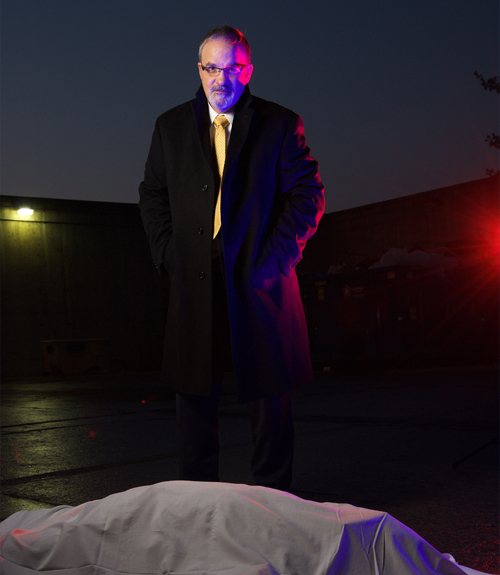

In his thirty-plus years as a forensic pathologist, Jentzen has handled dozens of high-profile and emotionally difficult cases. During that time, he has also sought to raise the standards of the field of forensic pathology through his work in outreach and education.

Jeffrey Jentzen, M.D., Ph.D. with Police Chief Philip Arreola(left) making an announcement involving the Jeffrey Dahmer case (1991)/Milwaukee Sentinel; Jentzen taking measurements for a case in Chicago involving a 16-year-old fatally shot (1993)/Jeffrey Phelps/Sentinel.When Jentzen began his anatomic and clinical pathology residency at the Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he knew little about the work of forensic pathologists. "That was in the era before CSI and all the crime shows," he says. "The Quincy TV show was out, but that was about everybody's limited experience with the field." Typically, medical students and pathology residents have little exposure to the field unless their program is connected--as UMHS' is--with a medical examiner's office. As it happened, the chair of Jentzen's department, John Coe, was also the county's medical examiner. Coe had even been part of the congressional select committee that answered questions about the deaths of President John F. Kennedy and Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. In his earliest years as a pathologist, Jentzen learned from one of the leaders in the field.

During training, Jentzen attended numerous death scenes. This is not typical of forensic pathology fellows, but it was a requirement in Minneapolis. Though Jentzen has sharp memories of being outside in negative 45-degree Minnesota weather, he grew to appreciate the unique experience. "'Autopsy' means 'to see for oneself,'" Jentzen says, "and that's what going to a crime scene is, too." The scene provides a perspective that might not otherwise be available. For example, viewing the position of the body at the scene of the crime, can help a pathologist better understand how an injury occurred.

During his residency and fellowship, Jentzen was also able to assist his mentor Coe with early investigations of vitreous fluid, and he learned about post-mortem drug redistribution. ("It's important to recover blood specimens in the peripheral blood vessels rather than around the heart," says Jentzen.)

(Left to Right) Jeffrey L. Dahmer/Milwaukee Sentinel; Drew Peterson/Detroit Free Press; Plane down in Lake Michigan resulting in the death of six people/Benny Sieu/Sentinel Journal. At the age of 33, Jentzen became Milwaukee County's medical examiner. This was 1987, and he was one of the youngest medical examiners of a major American city. He would eventually go on to handle high-profile cases, such as the Jeffrey Dahmer serial killing in 1991, and the Milwaukee heatwave in 1995, when 100 people died suddenly in a single night. But his most lasting contributions to the field include his efforts to raise national standards.

In 1995, while vacationing with a childhood friend who has a Ph.D. in curriculum design, Jentzen expressed frustration that there were no formal measures of investigator performance and training. Death investigators need a combination of skills in the areas of medicine and law in order to investigate bodies at the scene. Working together, the two men went on to create a training manual and test, which eventually developed into the American Board of Medico-Legal Death Investigation. Jentzen also worked with the National Association of Medical Examiners to develop national forensic autopsy standards. Until 2006, there was no official standard. A forensic autopsy could be anything from opening a skull and looking at the brain, to a complete full-body autopsy.

While working as the medical examiner for Milwaukee County, Jentzen obtained a Ph.D. in the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. His most recent publication, Death Investigation in America: Coroners, Medical Examiners, and the Search for Reasonable Medical Certainty is a history of forensic pathology in America published by Harvard University Press (2009). He currently completing another book, Instruments of Empire: A Global History of Colonial Legal Medicine also by Harvard Press.

Photography: Elizabeth Walker, Pathology Imaging Specialist

Since joining the U-M in 2008, Jentzen has continued his innovative work. He and his team have worked with Gift-of-Life, an organ- and tissue-recovery program, developing an automated reporting system that allows the Health System to make timely notifications about donor availability. As a result, Washtenaw County has the highest number of cases for organ and tissue recovery in the nation. Hospitals around the country have used this program as a model.

Jentzen also collaborates with his U-M colleagues. He is currently working with the U-M International Center for Automotive Medicine on a program to understand injuries involved in pedestrian fatalities, which have gone up 40% over the last 10 years. During the H1N1 outbreak, he partnered with intensive care specialists, conducting autopsies to understand why some people died of the illness while others survived. Working at University Hospital, his group of pathology residents identified a marker in the blood associated with death. Subsequent studies identified a related genetic mutation, suggesting that some individuals may be predisposed to die from that particular flu strain.

Over the years, Jentzen has greatly influenced his field, and he continues to bring positive change to the Department of Pathology.

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Breast team reviewing a patient's slide. (From left to right) Ghassan Allo, Fellow; Laura Walters, Clinical Lecturer; Celina Kleer, Professor. See Article 2014Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Autopsy Technician draws blood while working in the Wayne County morgue. See Article 2016Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Sriram Venneti, MD, PhD and Postdoctoral Fellow, Chan Chung, PhD investigate pediatric brain cancer. See Article 2017Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Director of the Neuropathology Fellowship, Dr. Sandra Camelo-Piragua serves on the Patient and Family Advisory Council. 2018Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Residents Ashley Bradt (left) and William Perry work at a multi-headed scope in our new facility. 2019Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Kristine Konopka (right) instructing residents while using a multi-headed microscope. 2020Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Patient specimens poised for COVID-19 PCR testing. 2021Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Dr. Pantanowitz demonstrates using machine learning in analyzing slides. 2022Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

(Left to Right) Drs. Angela Wu, Laura Lamps, and Maria Westerhoff. 2023Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

ON THE COVER

ON THE COVER

Illustration representing the various machines and processing used within our labs. 2024Department Chair |

newsletter

INSIDE PATHOLOGYAbout Our NewsletterInside Pathology is an newsletter published by the Chairman's Office to bring news and updates from inside the department's research and to become familiar with those leading it. It is our hope that those who read it will enjoy hearing about those new and familiar, and perhaps help in furthering our research. CONTENTS

|

MLabs, established in 1985, functions as a portal to provide pathologists, hospitals. and other reference laboratories access to the faculty, staff and laboratories of the University of Michigan Health System’s Department of Pathology. MLabs is a recognized leader for advanced molecular diagnostic testing, helpful consultants and exceptional customer service.